On fine days Maurice Garin could often be found sitting in the office doorway of his service station on rue de Lille in Lens. A sign above the garage, depicting a cyclist, bore a caption proudly proclaiming “Road Champion of the World”.

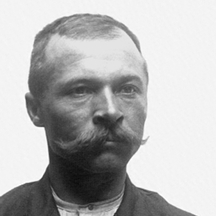

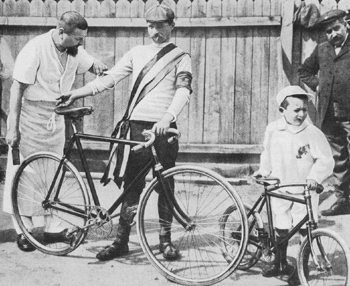

In his day, Garin had been described as possessing diabolical power and a shrewd racing brain. Now, well into his 80’s, a small yet still vigorous man with a perfectly groomed moustache, Le Père Garin would sit and watch as the children of the town raced past on their bicycles in tight formation, trying to impress the one time champion. Although his career was to end in controversy, Garin had come from humble beginnings and progressed to become the strongest rider of his day, winning many of the big races, including the very first edition of the Tour de France.

In his day, Garin had been described as possessing diabolical power and a shrewd racing brain. Now, well into his 80’s, a small yet still vigorous man with a perfectly groomed moustache, Le Père Garin would sit and watch as the children of the town raced past on their bicycles in tight formation, trying to impress the one time champion. Although his career was to end in controversy, Garin had come from humble beginnings and progressed to become the strongest rider of his day, winning many of the big races, including the very first edition of the Tour de France.

Born on March 3rd 1871 in Arvier, a French speaking village in the Aosta Valley of North West Italy, Maurice-François Garin was the eldest son of Maurice-Clément Garin, a labourer and his young wife, hotel worker Maria Terasa Ozello. Little is known about Garin's early life. The late 19th century saw the height of the Italian Diaspora, the mass migration of Italians fleeing poverty in search or work. The authorities had requested that mayors of the area make it difficult for families to leave, forcing those that did, to do so in secret. It was common at the time for unscrupulous padrones to come to rural areas recruiting children from poor families who would be exploited for their labour in foreign lands. The Garin family it seems had decided to seek a better life beyond the Alps, they separated and, aged 14, if legend is to be believed, Maurice was apprenticed as a chimney sweep to such a padrone in exchange for a round of cheese.

By 1889, Garin, still a chimney sweep, had made his way to Maubeuge following spells in Reims and Carleroi in Belgium. It was here that Garin purchased his first bike. At a cost of 405 francs it equated to twice the average monthly wage for a forge worker working 12 hours a day six days a week. Maurice had no interest in racing at first, but soon earned himself a reputation as a madman due to the crazy speeds he rode around town. In 1892 he acquired French nationality. He had also caught the eye of the secretary of the local Maubeuge Cycling club who persuaded him to take part in the 200km Maubeuge-Hirson-Maubeuge race. Despite suffering from the effects of the sun, Garin finished 5th, good enough to encourage him to continue racing. Maurice began training, frequently riding late into the night.

Garin deemed his bike too heavy for racing so he replaced it with a lighter model, costing him 850 francs. Although lighter than his first bike it still weighed in at a rather hefty 16kg. In 1893 Garin won his first race in Belgium, the 102 km Namur-Dinant-Givet. During the race he suffered a puncture near Dinant forcing him to leave his own bike behind and take a spare bike from a soigneur who was waiting by the road for another rider. He went on to win the race by a clear 10 minute margin. After the race he returned the bike to its rightful owner and went back to retrieve his own bike from where he had left it leaned against the wall of a bridge.

As well as being a strong rider Garin was a skilled mechanic, a vital skill to have in races of the day. He did all of his own maintenance including improving his wooden wheels to make them stronger and better running on bumpy roads and strengthening weak inner tubes by glueing the canvas from kerosene lamp wicks to them.

In his early years Garin showed himself to be an exceptionally strong rider, excelling in long races. Despite his success, however, he still refused to turn pro. He finally relented in typically unusual circumstances when he turned up for a race in Avesnes-sur-helpes, 25 km from his home in Maubeuge. The race was for professionals only and he was refused entry. Undeterred, he let the race start, rolled up behind the peleton and passed them. Despite falling off twice he won the race by some considerable margin much to the delight of the crowd. The organisers where somewhat less delighted however and refused to pay him the 150 franc prize money. The spectators clubbed together and presented Maurice with 300 francs in appreciation of his efforts.

In 1895 he moved to Roubaix and opened cycle shop with 2 of his brothers, Francois and Cesar, also proficient a cyclist. Having finally turned pro, he won his first professional race in 1895, a 24 hour event in Paris organised by Le Velo newspaper. Held on a particularly cold February day in front of few spectators, the weather was to take its toll on the riders as they dropped out one by one. Garin won the race after completing a distance of 701 km, some 49km more than the only other finisher, the Englishman Williams. Garin attributed his win to feeding properly. He avoided the strong red wine popular with most competitors of the day. During the course of the race he consumed 19 litres of hot chocolate, 7 litres of tea, 8 eggs, a mixture of coffee and champagne, 45 rib cutlets, 5 litres of tapioca, 2 kg of rice pudding and oysters. His win was to catch the eye of a certain Henri Desgrange who, 8 years later, would organise the first Tour de France.

In 1895 he moved to Roubaix and opened cycle shop with 2 of his brothers, Francois and Cesar, also proficient a cyclist. Having finally turned pro, he won his first professional race in 1895, a 24 hour event in Paris organised by Le Velo newspaper. Held on a particularly cold February day in front of few spectators, the weather was to take its toll on the riders as they dropped out one by one. Garin won the race after completing a distance of 701 km, some 49km more than the only other finisher, the Englishman Williams. Garin attributed his win to feeding properly. He avoided the strong red wine popular with most competitors of the day. During the course of the race he consumed 19 litres of hot chocolate, 7 litres of tea, 8 eggs, a mixture of coffee and champagne, 45 rib cutlets, 5 litres of tapioca, 2 kg of rice pudding and oysters. His win was to catch the eye of a certain Henri Desgrange who, 8 years later, would organise the first Tour de France.

The next year, Garin was to finish third in the first ever Paris-Roubaix, 15 minutes behind winner Josef Fischer. He would have finished second had he not been knocked off his bike in a crash between two tandems including his own pace bike. He was however, to win the next edition beating Dutchman Mathieu Cordang in a thrilling finish over the last two kilometres of the velodrome at Roubaix:

“As the two champions appeared they were greeted by a frenzy of excitement and everyone was on their feet to acclaim the two heroes. It was difficult to recognise them. Garin was first, followed by the mud-soaked figure of Cordang. Suddenly, to the stupefaction of everyone, Cordang slipped and fell on the velodrome's cement surface. Garin could not believe his luck. By the time Cordang was back on his bike, he had lost 100 metres. There remained six laps to cover. Two miserable kilometres in which to catch Garin. The crowd held its breath as they watched the incredible pursuit match. The bell rang out. One lap, there remained one lap. 333 metres for Garin, who had a lead of 30 metres on the Batave.

A classic victory was within his grasp but he could almost feel his adversary's breath on his neck. Somehow Garin held >on to his lead of two metres, two little metres for a legendary victory. The stands exploded and the ovation united the two men. Garin exulted under the cheers of the crowd. Cordang cried bitter tears of disappointment.” - Sergent, Pascal (1997), trans Yates, D., A Century of Paris–Roubaix, Bromley Books, UK, ISBN 0953172902

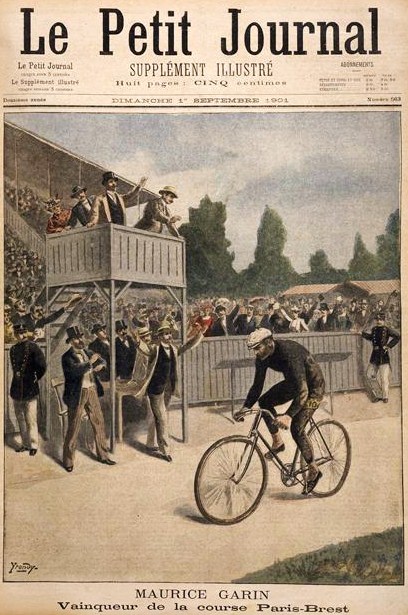

During his career, Garin won Paris-Mons; Paris-Cabourg, Paris-Royan, Paris-Roubaix (twice), and Bordeaux-Paris in 1901. He also won Paris-Brest-Paris, travelling 1200 km in 52 hours 11 minutes, almost 2 hours quicker than his nearest rival.

In 1903 Henri Desgrange, editor of L’Auto newspaper, was to organise the first Tour de France. L’Auto was suffering from stagnating sales, falling well behind its main rival, Le Velo, the largest nespaper in France with a circulation of 80 000 a day. Chief cycling journalist,Géo Lefèvre, proposed the Tour as a way to promote the newspaper. It was a hugely ambitious plan, cycling and cycle racing was hugely popular in France at this time, but nothing of this scale had ever been attempted. Originally the race was to be 5 weeks but this proved too daunting and only 15 riders entered. Desgrange shortened the race to 19 days, reduced the entrance fee from 20 to 10 francs, increased the prize money for the winner to 3000 francs and offered a 5 F daily allowance to the first 50 finishers. Encouraged by the increased stakes, 60 racers started the race which was run over 6 stages covering 2,428 km with 5 of the six stages being over 400km in length. Garin won the first stage and held his overall lead to the end. He cemented his victory by winning the last two stages, the final stage being the longest of the race, a mammoth 471km from Nantes to Paris. Garin won in a time of 94hours 33 mins averaging 25.679km/hr on a 16kg fixed wheel bike, 2h 59m 21s ahead of nearest rival Lucien Pothier. Garin’s winnings for the race totalled 6,125 F.

In 1903 Henri Desgrange, editor of L’Auto newspaper, was to organise the first Tour de France. L’Auto was suffering from stagnating sales, falling well behind its main rival, Le Velo, the largest nespaper in France with a circulation of 80 000 a day. Chief cycling journalist,Géo Lefèvre, proposed the Tour as a way to promote the newspaper. It was a hugely ambitious plan, cycling and cycle racing was hugely popular in France at this time, but nothing of this scale had ever been attempted. Originally the race was to be 5 weeks but this proved too daunting and only 15 riders entered. Desgrange shortened the race to 19 days, reduced the entrance fee from 20 to 10 francs, increased the prize money for the winner to 3000 francs and offered a 5 F daily allowance to the first 50 finishers. Encouraged by the increased stakes, 60 racers started the race which was run over 6 stages covering 2,428 km with 5 of the six stages being over 400km in length. Garin won the first stage and held his overall lead to the end. He cemented his victory by winning the last two stages, the final stage being the longest of the race, a mammoth 471km from Nantes to Paris. Garin won in a time of 94hours 33 mins averaging 25.679km/hr on a 16kg fixed wheel bike, 2h 59m 21s ahead of nearest rival Lucien Pothier. Garin’s winnings for the race totalled 6,125 F.

The first Tour had been so successful, the organisers did not hesitate in organising a second, the following year, following much the same route and format as the first. The race, however, was to fall victim to its own popularity. Scandal abounded with allegations of riders cheating, stories of over enthusiastic spectators felling trees, laying tacks and physically assaulting riders in an attempt to slow rivals and give their favourites an advantage. At one point, Garin and his brothers were set upon by an angry mob, the crowds anger possibly fuelled by reports that Garin had accepted food illegally from a race official Lefevre. Garin himself was wounded in the fracas which was only broken up when officials and police arrived, firing revolvers into the air. Garin was prompted to state: “I'll win the Tour de France provided I'm not murdered before we get to Paris.”

Garin did indeed finish first, 6 minutes ahead of the second placed Lucien Pothier. However amidst accusations of riding in cars and taking trains and after months of investigation and statements from witnesses the Union Vélocipédique Française disqualified the first 4 in the General Classification and all stage winners. A total of 11 of the 27 racers who finished were disqualified, making fifth placed Henri Cornet the winner aged 19. Desgrange was outraged and protested the decision. The heated exchanges between Desgrange and the UVF and also the exact reasons for Gains dismissal and suspension have long been lost since the official documents of the Tour were moved south in 1940 to protect them from the invading Germans. Although undoubtedly the strongest rider of his day, the authorities felt they needed to make an example of the champion to prevent the new race and the sport of cycling falling further into disrepute, they therefore issued Garin with a two year ban. Desgrange vowed never to hold another Tour de France again. Garin for his part publicly maintained his innocence throughout his life, although in his latter years, he allegedly admitted to a friend in private to taking a train.

Now aged 34, the two year ban he received after the 1904 Tour effectively ended his riding career. The little chimney sweep, this small, stocky rider and his beautiful moustache, who’d won all of the most important races of his day, was never to be seen at the head of the peleton again. In 1902 Garin had moved to Lens. It was here that he purchased a service station from his winnings on the road and lived out the rest of his years. Despite never racing again, Garin maintained an interest in cycling. In 1949 he returned to his birthplace to see the Tour pass through and, after the second world war, ran a professional team under his name. In 1953 he was invited to join several old stars at the finish of the Tour to celebrate its 50th anniversary. Maurice Garin died on February 19th 1957 aged 85.